What % Schizophrenics in Pop Convicted of Homicide vs General Pop?, and Speculations On How To Reduce Homicides And Other Violence During Psychosis

"0.4%" or "0.5%" answers the question posed by Study 2, and "5%" answers the question posed by Study 1 | Homicides ~15x likelier during FEP than *after treatment for psychosis* | ~5030 Words

{I didn’t access full texts for most of the studies linked. Also disclaimer — this post is brought to you by some of my fears.}

I.

I wrote this not because I believe this can help reduce the current homicide rate in Ontario, but because I felt compelled to for my own peace of mind.

I began having violent outbursts for the first time during the onset of first-episode psychosis, and have never had them ever since I was put on antipsychotics for the first time in September-October 2023. I believe I currently have strong medication adherence. But I still have fears about worst case scenarios if I for some reason I ever descend into the throes of psychosis again.

(Some people never become violent during psychosis. Unfortunately, I’m not included in this group.)

A persistent fear at the back of my mind is that I could be at higher risk of committing homicide than the average person. Committing homicide during psychosis — and being sent to prison for manslaughter, and having to live with that guilt for the rest of my life — is one of my biggest fears, and I would REALLY, REALLY, REALLY like to lower the risk of that ever happening.

What percent of people who are convicted of homicides have been identified as schizophrenic?

Study 1 (England & Wales):

“A national clinical survey of people convicted of homicide (n=1594) in England and Wales (1996-1999). Rates of mental disorder were estimated based on: lifetime diagnosis, mental illness at the time of the offence, contact with psychiatric services, diminished responsibility verdict and hospital disposal.”

“Of the 1594,545 (34%) had a mental disorder: most had not attended psychiatric services; 85 (5%) had schizophrenia (lifetime); 164 (10%) had symptoms of mental illness at the time of the offence; 149 (9%) received a diminished responsibility verdict and 111 (7%) a hospital disposal - both were associated with severe mental illness and symptoms of psychosis.”

Another study (meta-analysis):

“We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies conducted in developed countries of homicide committed by persons diagnosed with schizophrenia.

…

We found that rates of homicide by people diagnosed with schizophrenia were strongly correlated with total homicide rates (R=0.868, two tailed, P<0.001). Using meta-analysis, a pooled proportion of 6.48% of all homicide offenders had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (95% confidence intervals [CI]=5.56%-7.54%).”

Another study (Russia):

“There are few studies of the relationship between mental disorder and homicide offences from regions with high rates of homicide. We examined the characteristics and psychiatric diagnoses of homicide offenders from the Chuvash Republic of the Russian Federation, a region of Russia with a high total homicide rate. In the 30 years between 1981 and 2010, 3414 homicide offenders were the subjected to pre-trial evaluations by experienced psychiatrists, almost half of whom (1596, 46.7%) met the international classification of diseases (ICD) 10 criteria for at least one mental disorder. The six most common individual diagnoses were alcohol dependence (15.9%), acquired organic mental disorder (7.3%), personality disorder (7.1%), schizophrenia (4.4%) and intellectual disability (3.6%). More than one disorder was found in 7.4% of offenders and alcohol dependence was the most frequently diagnosed co-morbid disorder.”

Common rhetoric is that schizophrenia occurs at an incidence of about 1% within the general population.

I searched a little through Google for studies on prevalence of schizophrenia in the general population in Russia in the years 1981-2010 to compare to the prevalence of schizophrenia in homicide offenders (4.4%) in the Chuvash Republic of Russia at that time, but did not find any studies.

I also searched for studies on the prevalence of schizophrenia in the general population in England and Wales in the years 1996-1999, to compare this prevalence to the prevalence of schizophrenia in those who were convicted of homicide (5% according to Study 1) in those locations, and during that timeframe.

The closest I found was Study 2, which mentions:

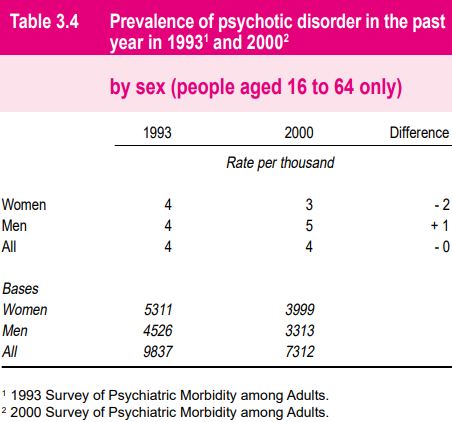

"The overall prevalence of psychotic disorder, applying the approach for ascertaining cases used in 1993, was the same in 1993 and 2000: 4 cases per 1,000 adults aged 16 to 64 years."

Which clocks out to 0.4% (Study 2), while 5%; is the prevalence of schizophrenia found in people convicted of homicide according to Study 1 (FYI: 5% is 12.5 times more than 0.4%).

Confusingly to me, elsewhere, the report says:

“The prevalence rate for probable psychotic disorder in the past year was 5 per 1,000 adults aged 16 to 74. The rate among women was 5 per 1,000 and among men, 6 per 1,000.”

The charts they provide with this sample of 8580 participants show agreement with these rates.

Anywho, we’ll look at the sample of 8580 people, since nearly all of the data is given to us on this sample in particular.

Note that two general estimates were produced (…by researchers, I guess? By psychologists?) for psychosis prevalence. There are two estimates in which one estimate (estimate 1, “including screen negatives”) is determined using one methodology, and includes one sample, while estimate 2 (“screen negatives assumed negative”) uses a slightly different methodology and sample.

Initially, interviewers gave participants a first test to screen for psychosis, in which “The presence of any one of these criteria was sufficient for a person to screen positive for psychosis”:

“a self-reported diagnosis or symptoms (such as mood swings or hearing voices) indicative of psychotic disorder;

receiving anti-psychotic medication;

a history of admission to a mental hospital;

a positive answer to question 5a in the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire which refers to auditory hallucinations.”

Only those who screened positive for psychosis were included in estimate 2, which is the estimate that was used throughout the report (I’m guessing this 0.53% is where the 0.5% comes from).

However, a subsample of people who screened negative for psychosis using the first test (“screen negatives”) were given a second test, which found people who screened positive for the second test while screening negative for the first test; these people were thereby known as “false negatives”. These people were included in estimate 1 (the estimate with the higher prevalence of psychotic disorders, 1.11%), and not estimate 2.

(There were other differences in the populations included for the estimates, however the report is lowkey a PITA to read, and I think would be hard to summarize (it’s already pretty summarized), so I’m only including the gist of their methodology.)

Estimate 1 also used a wider range of sampling weights, which resulted in wider confidence intervals.

They (alas, the nebulous ‘they’ is used when I don’t know who’s involved in what) defend their choice of using estimate 2 throughout the report:

“The finding of some screen negatives does suggest that a prevalence rate based solely on screen positives (estimate 2) is likely to be an underestimate. However, in view of the wide confidence interval, it is also quite possible that estimate 1, which includes the screen negatives, may be itself a substantial overestimate. Therefore, it was decided that it would not be useful to use the prevalence estimate which includes the SCAN data from screen negatives in the report because of the imprecision and uncertainty associated with it. It is recognised that any estimate that does not take account of false negatives on the screen will be an underestimate, but the extent of that underestimate and the importance of it is uncertain. However, the estimate adopted is more stable and therefore more use for policy analysis and monitoring trends.”

Of course, if we’re looking to compare the % of schizophrenics using the criteria for study inclusion in Study 1 (of which be convicted of homicide is one criterion) to the % of schizophrenics using the criteria for Study 2, we’d be comparing apples to oranges. Among the potential extraneous differences between the studies, the ones I’ve noticed are:

Re: criteria (eg symptoms) being identified (both used ICD-10 AFAIK):

Study 2 sought the prevalence of ‘psychosis prevalence’ and ‘probable psychotic disorder’ for which they found 0.5%, and of ‘psychotic disorder’ for which they found 0.4%

Study 1 sought for 'lifetime history of schizophrenia' (ICD-10 is in their references_

For how long in their lives ie what duration of time in their lives did people meet the criteria sought for?

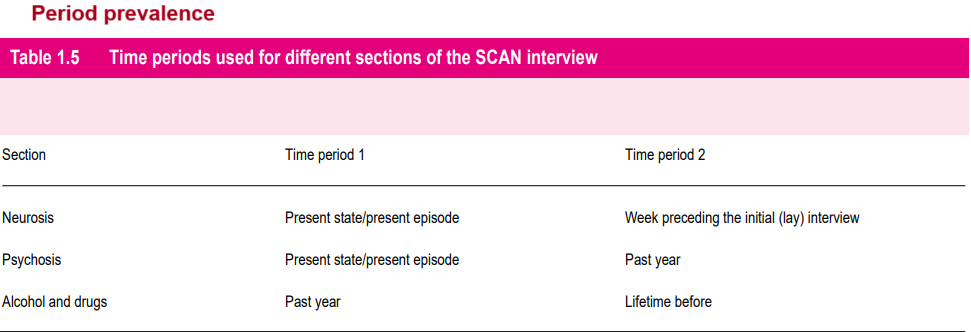

Study 2 looked for period prevalence (I guess excluding people who fulfilled the criteria for a psychotic disorder earlier in their lives but no longer do; though is this exclusion really A Big Deal?)

Study 1 looked for lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia

Year/s participants were surveyed

Study 2 surveyed people in 1993 and in 2000

Study 1 surveyed people in 1999 and possibly 1996 +/ 1997 +/ 1998

Participant location (& number)

Study 2 - 7247 people living in England, 921 in Scotland, 412 Wales, 8580 participants total

Study 1 - 1594 people in England and Wales

The difference in the populations studied is also not a clear-cut division between “convicted of homicide” (Study 1) or “not convicted of homicide” (what ideally, we’d have in the second study). Sure, study 1 surveyed people convicted of homicide. However Study 2 surveyed people living in private households. (Are there people convicted of homicide living in private households? Hopefully the answer to this is also Not a Big Deal.)

Anywho, using 5% and 0.4% or 0.5%, we can say the rate of schizophrenics is 10x or 12.5x higher among those convicted of homicide in Study 1 than among those living in private households included in Study 2.

II.

What are some possible tendencies of people with schizophrenia who’ve been convicted of homicide vs. people without schizophrenia who’ve been convicted of homicide?

“This study examines whether crime scene behaviors in Finnish homicides are associated with differences in offenders' mental status. Homicide crime scene behaviors were analyzed among five groups of offenders: those with schizophrenia, those with personality disorder, drug addicts, alcoholics, and offenders without a diagnosis (N= 182). The results showed that crime scene behaviors, victim gender, and victim-offender relationship differed between the mentioned groups. In particular, schizophrenic offenders and drug addicts had some unique features in their crime scene behaviors and choice of victims. Schizophrenic offenders were more likely to kill a blood relative, to use a sharp weapon, and to injure the victim's face. Drug addicts more frequently stole from the victim and tried to cover up the body. Results are discussed in terms of their utility to criminal investigation.”

“Results: Of the 3930 homicide perpetrators identified, over a third (36%) used a sharp instrument. The use of firearms was rare. Methods of homicide differed significantly between diagnostic groups. Perpetrators with schizophrenia were more likely to use a sharp instrument and predominantly killed a family member or spouse in the home; a significant majority were mentally ill at the time of the offence. Perpetrators diagnosed with affective disorder were more likely to use strangulation or suffocation. Alcohol dependent perpetrators used hitting or kicking significantly more often, primarily to kill acquaintances.”

What are some differences between schizophrenics who have been convicted of homicide and schizophrenics who haven’t been convicted of homicide?

During the observation period 160 male patients with schizophrenia and a history of psychiatric admission were convicted of homicide, and they were matched with 542 male control patients who had not been convicted of homicide. Patients who committed homicide were more likely to have a history of violence and comorbid personality disorder or drug misuse. They were more likely to have missed their last contact with services prior to the offence and to have been non-adherent with their treatment plan. Almost all (94%) of homicides were committed by patients who had a history of alcohol or drug misuse and/or who were not in receipt of planned treatment.

However, I’m not the only part of the problem.

During first-episode psychosis is when a disproportionate amount of homicides occur. It is a time when substantial number of people have no idea they’re experiencing psychosis at all (which was in my case), and are not taking antipsychotics.

“A systematic search located 10 studies that reported details of all the homicide offenders with a psychotic illness within a known population during a specified period and reported the number of people who had received treatment prior to the offense. Meta-analysis of these studies showed that 38.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 31.1%–46.5%) of homicides occurred during the first episode of psychosis, prior to initial treatment. Homicides during first-episode psychosis occurred at a rate of 1.59 homicides per 1000 (95% CI = 1.06–2.40), equivalent to 1 in 629 presentations. The annual rate of homicide after treatment for psychosis was 0.11 homicides per 1000 patients (95% CI = 0.07–0.16), equivalent to 1 homicide in 9090 patients with schizophrenia per year. The rate ratio of homicide in the first episode of psychosis in these studies was 15.5 (95% CI = 11.0–21.7) times the annual rate of homicide after treatment for psychosis.”"

“In the 10 years from 1993 to 2002, there were at least 88 people charged with 93 homicide offences committed during the acute phase of mental illness. High rates of drug misuse, especially of drugs known to induce psychotic illness and brain injury, were reported. Evolving auditory hallucinations and delusional beliefs that led the person to believe they were in danger were the symptoms strongly associated with lethal assault. The victims were mostly family members or close associates. Only nine of the victims were strangers, including three fellow patients. Most lethal assaults (69%) occurred during the first year of illness, and the first episode of psychotic illness was found to carry the greatest risk of committing homicide.”

III.

kuebiko n. a state of exhaustion inspired by an act of senseless violence, which forces you to revise your image of what can happen in this world—mending the fences of your expectations, weeding out invasive truths, cultivating the perennial good that’s buried under the surface—before propping yourself up in the middle of it like an old scarecrow, who’s bursting at the seams but powerless to do anything but stand there and watch. — Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

Re: the blurb above — I’ve seen this word in the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. I will say though, I believe we are not without options to reduce this risk of homicide — and violence in general — perpetrated by sufferers of psychosis.

I don’t which humans are more responsible for this: Teach more about signs and symptoms of psychosis, and the prodrome of schizophrenia as part of the elementary and high school curriculum.

When I was in Grade 9, I remember learning, “If you do cocaine, you could DIE THE VERY FIRST TIME!!!” in health class in school — they literally showed us a video of an adolescent who used cocaine for the first time, was taken into an ambulance, and died shortly after.

I also remember learning from Health and Physical Education, “Smoking has these terrible health effects and HERE ARE ALL THE WAYS TO SAY NO TO SMOKING!! DON’T GIVE INTO PEER PRESSURE!” I think they actually taught us a lot on risks of smoking. Or maybe I just feel this way because I got assigned it as a PowerPoint presentation I had to do in Grade 9.

I don’t remember learning anything like, "Here are signs you or someone you know may be experiencing psychosis”.

Bitterly, I ask nobody in particular, why does it take committing a particular violent crime for me to be identified as in psychosis after having been in psychosis for over 978 days?

During the time I have been in first-episode psychosis, I estimate that >50-100 people through online interactions witnessed me behave in what — looking back, to me are now recognizably psychotic ways. Maybe if people everywhere knew more about the signs of psychosis, somebody would have suggested that I was experiencing psychosis, and possibly that could bring me closer to seeking treatment (before violence ever escalated).

I think it’s safe to say that since I was in elementary and high school, more things are being taught related to mental health in the Health and Physical Education (HPE) curriculum.

The Government of Ontario held a consultation on the publicly funded education system in 2018. They made the most recent curriculum for Health and Physical Education (HPE) for Grades 1-8 in 2019, and it was “informed by the results of the consultation, as well as research and learnings from other jurisdictions”.

“For Grades 1-8, Ontario’s updated HPE curriculum now includes “mandatory learning about mental health”.

They go a little into more detail into what’s taught in each grade (starting September 2019), with “mental illness” being something that’s covered in the Grade 7 curriculum. But I didn’t find anything more specific than mental illness.

Moreover, “The Ontario government is also announcing an increase in mental health funding in schools to a historic $114 million in 2023-24, representing an over 500 per cent increase since 2018.” They go on to write, on May 01, 2023:

“Announced at the start of National Mental Health Week and proposed for introduction in schools in the next school year, the new mandatory mental health literacy resources will include:

New learning materials for Grade 7 and 8 students that are aligned with the Health and Physical Education curriculum. This includes important tools like student activities, videos and interactive programming and information that will help students learn how to manage stress, understand the relationship between mental health and mental illness, recognize the signs and symptoms of a mental health concern, counteract mental health stigma and know when and how to get help.

Mandatory learning on mental health literacy for Grade 10 students will start in fall 2024 and will include how to recognize signs of being overwhelmed or struggling, as well as where to find help locally when needed. This will be included in the Career Studies course.”

I think this might be helpful for the societal (it’s everyone’s responsibility) early detection of psychosis. But I’m afraid they’ll neglect to mention it, as psychosis is one of the rarer phenomena. There’s a lot more added about mental health that I would want to see as part of the curriculum as well. I’m extremely biased, of course.

I don’t know what’s being pushed out of the curriculum, if anything is.

Reflecting on this now at age 27, I don’t think any of the information I learned in the Career Studies course in Grade 10 has helped me with life. Personally, I’d be more than thrilled if the entire course was replaced by a course on mental health. So I’m glad that that the Career Studies course will include “how to recognize signs of being overwhelmed or struggling”. I don’t know what “mental health literacy” refers to exactly, but it sounds like it could be useful.

Meanwhile, the Health and Physical Education curriculum for Grades 9-12 has been unchanged since 2015 (the year I graduated high school). Students only need to have “one compulsory credit in health and physical education towards their Ontario Secondary School Diploma”, and of the four open Healthy Active Living Education (HALE) courses, only Grade 11 has any mention of schizophrenia (there are 4 search results for “schizophrenia” in the pdf linked).

And even in that Grade 11 curriculum, I doubt there will be enough hours spent on learning about psychosis and schizophrenia to help someone recognize in the future if they or someone they know are experiencing psychosis.

(At least the curriculum is going in a direction I like.)

I know it sounds silly, but I remember there being a lot of wall space in school. I don’t know why there aren’t year-long posters in elementary schools and high schools with posters with information about "Signs of depression", "Signs of anxiety", “Risks of smoking” and “Risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease” etc on the walls. Perhaps the more introverted and/or conscientious students will read posters on the walls from time to time.

I don’t think this is ridiculous. In entrances to locked units in LTCs, there are lots of papers posted on the walls of the facility pertaining to how to respond to someone exhibiting signs of dementia. I think they’re helpful for the institution to do its intended job.

I don’t which humans are more responsible for this: I’m not saying this is going to happen, because I don’t know anything — but provide individuals who live with their parents a decent place to stay so the choice of living away from parents becomes more appealing.

FYI, this isn’t just for the homeless.

It’s because parricides (homicides of either parent) happen often, and happen far more often when sufferers of psychosis live with their parents, in their parents’ house.

“Among patients with schizophrenia who were in the National Institute of Forensic Psychiatry between November and December 2007, 88 patients who committed homicides were enrolled; 59 had committed parricide, and 29 had killed strangers. Medical charts, written expert opinions, written records of police or prosecutors, and court decisions were reviewed. Direct interviews with patients were also conducted.”

“Significant factors associated with parricide among homicidal patients with schizophrenia were living with the victim, female sex of the victim, and offense-provoking events including scolding, threatening forced hospitalisation, and forcing medication on the patient before the homicide. Capgras syndrome was present at a significantly higher rate in the parricide group than in the stranger group. Drug compliance at the time of the offence was low in both groups.”

(Also, if you’re a parent of a schizophrenic, after reading the above, I would minimize scolding, threatening to hospitalize or forcing medication on them.)

Schizophrenic person: If you would kid-proof a house, why would you not psycho-proof a house?

Sometimes findings I read aren’t clear about how a violent crime was committed – if there was a weapon involved, where was the object used? Was it in an open, easy-to-reach space, and easily identifiable among other objects, or was it in a concealed location that requires more motor skills to reach, e.g., in a back corner of a drawer instead of in plain sight on a countertop?

If you’re living with someone who has schizophrenia, I wouldn’t suggest this to them unless they already have exhibited violent tendencies (and even still, this could be interpreted as offensive).

But if they have and wish to prevent further incidences of violence, it could be a good idea to suggest them to make dangerous items less accessible to themselves.

I find gross motor skills harder to perform in psychosis.

The person prone to psychosis can, when they’re not psychotic, move the “default" storage locations of items in the house to be places in which they’re less visible and accessible — because otherwise, those items could be the “first thing they see” & grab for when they experience a persecutory delusion, and (which isn’t in the case of all persecutory delusions, only some) are motivated to harm someone in response. This has happened once to me.

In my parents’ house, craft scissors are now in back of a cabinet instead of in a cylinder on the desk, and kitchen scissors are in the second-lowest drawer in a kitchen instead of the highest or second-highest drawer; further away from my arm-level.

Scissors are only left unconcealed if I currently need them or just after I’m done using them and before I put them back into their default storage location.

Colours also tend to “stick out” to people who are in psychosis.

Personally, I would avoid buying sharp objects that have colourful handles, and avoid placing dangerous objects in locations where they visually stick out against the background. Conceal objects that the mind easily recognizes as weapons (e.g., hammers, scissors) in some sort of opaque storage, instead of having them visible when you walk into and scan a room.

Schizophrenic person: Reduce time spent in proximity to dangerous objects (e.g., to knives in the kitchen) while another person is in the house.

Two of the types of violent acts I did during psychosis involved objects in the kitchen — 1-2 knives that had been thrown haphazardly (and had missed living targets) in one case, and a pair of scissors laying on the kitchen counter that was used for stabbing in the other case.

I had been obsessively into cooking — which included the prolific chopping of vegetables, e.g., carrots, cabbage, and butternut squash using kitchen knives — and meal-prepping during many months when I had been in unidentified psychosis in the second half of 2022 through the first half of 2023, and had also occasionally been hypomanic during those psychotic times, and had spent probably more time than the average person would in their kitchen and surrounding area.

Basically, if another living being could be around, which includes if they have the potential to pop into the premises from a room just around the corner (this is what happened during the time I stabbed my Dad with a pair of scissors), reduce time spent around items that you can easily identify as weapons, and that can be potentially dangerous if you feel anger and/or hatred with the sudden onset of a delusion.

Schizophrenic person: Read about the therapeutic and side effects of different antipsychotics, and bring up to your psychiatrist that you wish to try ones you haven’t before.

If the side effects of an antipsychotic is deterring you from taking your medication, there might be an antipsychotic that doesn’t have that side effect or has to a lesser extent.

People living with schizophrenics: Remind schizophrenics daily to take their meds.

Something that helps that my parents pick up my antipsychotics for me from the pharmacy, as I don’t have my driver’s license, and I have little motivation to do things that would even benefit me tremendously (such as walk 20 minutes to my nearest pharmacy to pick 60 days worth of antipsychotics). One of my parents frequently reminds me in the morning to take my medications, as well as in the evening when it’s time for dinner to take my medications.

People living with schizophrenics: if someone takes tablet antipsychotics daily or twice daily, avoid bringing up potentially confrontational subject matter around routine medication times, since those are the times when the effects of the last dose of antipsychotic are closer to wearing off.

The above are all speculations — maybe they would have no difference on rates of violence during psychosis at all, but I want to bring something up that is more contingent.

I can’t re-find the link to a study, though it didn't have more than 30 participants IIRC anyway. The study mentioned that before their first presentation to services, ~20-50% of participants IIRC had previous acts of violence that went without calls made. I find it believable that family members avoid making calls during initial bouts of violence due to wishing to avoid punishment for the perpetrating family member, as well as false hope that the perpetrator’s state is temporary, and that the domestic abuse will go away on its own. Personally, during FEP I attacked family members three separate times that went uncalled for, that retrospectively, I believe calls should have been made – including to police.

But is it good to have more people call or make calls earlier to the police or bring others to the ER more often?

It’s also not just that bringing people to the ER (some of whom may not be in psychosis) will get people treatment for psychosis, though perhaps connecting non-psychotic people to mental health services would be beneficial in some other way.

The first time I was handcuffed by police and involuntarily taken to the ER, I was formed, and given a 2-3 day involuntary stay. The date on my bag for “patient belongings” has August 16, 2023 written on it. I don’t remember seeing a psychiatrist, nor being given medication tablets, nor anyone bringing up the word “psychosis”, but my memory may not be reliable.

But certainly, nobody gave me any medication to take after being released. They released me as if I had been psychologically sound.

The violence I committed in the month after the August incident was nowhere near physically dangerous enough to take someone’s life, but had I done something that was, I would probably have had to spend the rest of my life in a psychiatric institution for what could have been prevented had the hospital identified and treated my condition the first time it presented itself to them.

Is it not worth it to screen a 26-year old brought by police into the ER for a violent incidence (throwing knives at parents) for the first time in their life, who has had ever since age 19 the diagnoses of GAD with obsessive-compulsive tendencies, MDD, and an eating disorder (the initial, “official”, and by four years the longest criteria-fitting diagnosis being AN-b/p, though at the ER in August I fit the criteria for BN) for first-episode psychosis, or was there an accidental or systematic oversight by the hospital? I ask this question literally.